This section is about about the various time units in dance music, and how they relate to concept you may know from dancing. There are the beats, which are similar to single dance steps. Taking a few beats together gives you a bar or measure, just like a few steps give you a pattern. Bars combine to give phrases, just as from a few patterns you build an amalgamation, and from phrases you build a song the way you string amalgamations together into a routine that will last a whole song.

However, the correspondence I have just sketched is only by analogy. This page will teach you exactly what the similarities and the differences are.

If you haven't done so already, please read the Introduction to music notation.

In conversations about music you will often hear the word beat. People will say This song has a good beat or The guitar has a intro of eight beats. In the first sense of the word beat is almost synonymous with rhythm, and that is a concept that we will go into later on. Right now we are focussing on the second sense, where beats are things you can somehow count. Here is the clearest example: if the band leader counts down "One, two, three, four!", he has just counted four beats. Beats, then, are the basic units of counting dance music. They are what you tap your foot to if the music has an infectuous rhythm.

How do you find what the beats are? In some music they are very easy to hear. For instance, in some bluesy music the bass may play a walking bass pattern. In disco music it is the bass drum that plays boom boom boom boom, one boom per beat. In such cases it is easy to find the beats: just count along with the instrument doing the "boom"ing.

In other cases there is no one instrument that you can listen to for the beat: you need to listen to the whole amalgam, and pick out the beat from that. Most of the times it will still be clear what the beat is, but in some cases people may disagree on precisely what are the beats.

A bar is a repeating group of beats, for example three counts in a waltz (this is called a ternary rhythm) and two or four counts in most other dances (this is called a binary rhythm). Usually you can easily recognise the bars.

![]() Waltz has a distinct "Oom pah pah" feeling,

that is, one heavy beat and two lighter ones. The heavy note is usually

played by the bass - reinforced by the bass drum of the drumkit, if one

is present - while the two lighter ones can be played by lighter sounding

instruments such as rhythm guitar in country waltz, or not be accentuated

at all in ballroom waltz. In that case you can tell the two light beats

only by listening to the vocal melody.

Waltz has a distinct "Oom pah pah" feeling,

that is, one heavy beat and two lighter ones. The heavy note is usually

played by the bass - reinforced by the bass drum of the drumkit, if one

is present - while the two lighter ones can be played by lighter sounding

instruments such as rhythm guitar in country waltz, or not be accentuated

at all in ballroom waltz. In that case you can tell the two light beats

only by listening to the vocal melody.

For the rhythms of most other dance the feel is "Left

Right" or "Up Down", that is, two beats. A lot of music has four beats to the bar, often

with a clear "left right left right" feel. But hold on a

second: "left right left right" is twice a repetition of two

beats. So why is this notated as one bar of four beats rather than two

of two? Partly it is a matter of convention and tradition whether binary rhythms are presented as having two or

four beats to the bar. Traditionally, Samba, Merengue, Polka, and Paso Doble are presented with two

beats to the bar; all other binary rhythms are notated with four beats

to the bar. Apart from convention there is another reason for notating

music with four beats to the bar; see below.

A lot of music has four beats to the bar, often

with a clear "left right left right" feel. But hold on a

second: "left right left right" is twice a repetition of two

beats. So why is this notated as one bar of four beats rather than two

of two? Partly it is a matter of convention and tradition whether binary rhythms are presented as having two or

four beats to the bar. Traditionally, Samba, Merengue, Polka, and Paso Doble are presented with two

beats to the bar; all other binary rhythms are notated with four beats

to the bar. Apart from convention there is another reason for notating

music with four beats to the bar; see below.

Musicians who start to dance are almost invariably puzzled, not to say confused, by the fact that music with four counts to the bar is used for dances that have six (as in swing, foxtrot, country two-step) or three (as in hustle) counts to the pattern. "It does not fit."

The thinking behind this confusion is something along the following lines. Music is a sequence of bars, and they are each counted the same way, for instance one two three four. Also, each bar has a rhythm that largely repeats in the next bar. Shouldn't dance patterns, which each have the same repeating rhythm, then also repeat, and in sync with the music?

In many dances, the rhythm of the basic pattern and the rhythm of the music are indeed closely matched. For instance, the rumba dance rhythm is Slow Quick Quick; this takes four counts, that is, exactly one bar, and it repeats the next bar. There is then an exact correspondence between one bar of music and one basic dance rhythm. A similar story holds for waltz, chacha, merengue, salsa, et cetera.

For these dances we can say that the start of a pattern always coincides with the start of a bar of music*. We do have to remark that for salsa and rumba every other pattern starts on the other foot (first you do a quick-quick-slow starting on the left foot, then quick-quick-slow starting on the right foot), so even though the basic rhythm repeats every bar, the footwork repeats only every other bar. Stil, even in these dances there is a simple correspondence between bars of music and dance patterns.

However, there are the dances mentioned above where no such simple alignment of dance patterns and bars of music exists. Basically, this observation is correct and there is no way around it. A single pattern can be shorter or longer than a bar of music, and that makes some patterns start on the bar, and others in the middle of a bar of music. There is nothing to do but to get used to this fact.

We can still salvage the alignment to an extent. Look at dances such as swing or foxtrot or country

two-step that have six-beat patterns. Two of these patterns together

fill up three whole bars of music. For example, in this example you

see two basics of country two-step, each counted QQSS. The

first basic runs to halfway the second bar, so the second basic starts

halfway the bar and runs till the end of the third. Now, the third

pattern -- and in general every other pattern -- will again start at

the beginning of a measure. In hustle the problem is slightly

different, but the solution is similar.

Such dances where the pattern has a different length from

the measure length are also confusing if you start counting. Do you count

the beats, or the steps? In dances like rumba there is no problem: you count

four beats per bar, and four beats per pattern. In a dance with a six-count

pattern you count four beats to the bar, but after four beats in the pattern

you still have two to go, while the musical count starts over at one. In

this example you see again two-step: the beats are counted over, and the

steps under, the rhythm. Most of the time, people count the dance steps,

not the beats, in such dances.

To make the dance bear a relation to

the music it is set to, good dancers will fit dance phrases to musical

phrases. For instance, a lot of music has 32 beats in each chorus or

verse, that is, eight bars. Now, above you saw that using six-count

patterns you can fill three bars exactly with two basic patterns. And

three bars does not divide in eight: two groups of three makes six

bars and you have two left. Fortunately, dances with six-count

patterns also have typically have eight-count patterns, and these help

you out.

A lot of western popular music is based on divisions in two and four. You already saw above how heavy and light beats alternate, and how a four-beat measure has a heavy and light alternation of such two-beat units. Another step up, a line in a song is often four bars long, and it goes on like this. We say that such songs, or the individual lines, have a binary structure.

On the very lowest level this division in twos manifests itself in backbeats and downbeats. Each bar of music typically has a "boom clap boom clap" feeling: the first and third beat (the down beats) have low frequency accents, while the second and fourth beat (the back beats) have high frequency accents. These accents do not concern the melody of the piece. Instead, we can trace them back to the rhythm section: the low frequencies are mostly in the bass and bass drum, while the high frequencies are mostly in the snare drum and rhythm guitar.

The downbeat/upbeat alternation can be heard over a wide range of tempos:

In many cases, every second heavy accent is not as heavy as the downbeat accent, for example because the bass drum does not play at the same time as the bass guitar (example: The Dazz Band, Let it whip). Another way in which this second heavy accent can be lighter is that the bass does not play the root of the chord, but another, secondary, note such as the fifth (example: just about any country two-step). More in the section about bass.

The binary structure of music continues on higher levels. Rather than calling it "heavy/light", a more appropriate description would be "tension/release". For instance, a line of a melody can have two clear halves, where the first half (Mustang Sally) asks for a resolution, which comes in the second half (Guess you better slow your mustang down). The binary structure is then continued with the second line, which echoes the first, often by simply repeating it with minor variations.

A rhythm is called ternary if the basic beats come in groups of three. This is usually easy to hear: the music has an "oom pa pa" feel to it. Waltz is the only ballroom dance with a ternary rhythm.

There is another example of ternary structure, namely the blues progression, which has three phrases of four bars each. More in the section about blues music.

On the highest structural level, a song can have one of several large scale structures. The two most common types are:

In both cases we have blocks of several lines, and it is these blocks that often have a binary division (though not blues melodies).

Apart from the main melody, a song can have an intro and a bridge passage.

The melodies of jazz standards have what is called an AABA structure. This means that the melody is divided in four sections, of which the first, second, and fourth are identical, while the third is different. Each of these four sections is one or two lines - sentences of the lyrics - long. A popular trick with ballroom orchestras is to start a melody with a latin rhythm, switch to swing/foxtrot for the "B" section, and switch back to latin for the final "A" section. Knowing this, you now know how to switch perfectly from one dance to the other, without ever having heard the band do this number before.

I should say a little more about jazz standards. These songs actually have a chorus and verse structure, but hardly anyone knows or sings the verses. Jazz instrumentalists definitely only repeat the chorus. (If they play an intro at all, it is a variation on the chorus melody.) You may come across such statements as "His solo lasted 10 chorusses." Just to confuse matters, this terms "chorus" is also applied to blues music to indicate one run-through of the blues progression, even though blues music does not have a verse and chorus structure.

If you are reading this course sequentially, which means that before this page you read the Introduction to music notation, you should now start reading up on the musical instruments.

Advanced topics

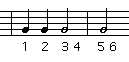

Sometimes it is open for debate what exactly the beats are in a

piece of music. One person may hear as one beat what another hears as

two beats. For instance, country two-step is a relatively fast dance,

so one person may hear beats that are approximately 1/3 second long,

and of which there are six in a pattern:  , while

someone else may count at half that speed, and conclude that a pattern

has three of these slower beats:

, while

someone else may count at half that speed, and conclude that a pattern

has three of these slower beats:  .

.

This problem occurs not just for two-step, the same question arises for the country dances pony and polka. The rules of the UCWDC put these dances at 110 and 120 bpm respectively, but I am of the opinion that that should be 220 and 240.

Counting at half speed is natural as music speeds up: as articulating one two three four becomes harder at high speeds, there is the temptation to "shift down a gear" and count at half speed. Likewise, for very slow music there is the temptation to count at double the real speed.

In a way, the question of what the "real" tempo of a piece of music is can not be settled unambiguously. Music notation is flexible, and any piece of music can be written any number of ways. However, in the context of dance music we can bring other considerations to bear.

A lot of dance music, and certainly anything country and western, is backbeat-based. That is, there is a recognisable alteration of downbeats, characterised by a note on the bass drum and/or bass guitar, and backbeats, almost invariably with an accent on the snare drum. For dances such as West Coast Swing, Hustle, Chacha, everyone agrees that they are around 120 bpm, and this tempo agrees with the snare drum pattern you typically hear. For Nightclub Two-step, most people agree that it is around 65 bpm, although I have heard of people dancing foxtrot to a slow N2S song, and claiming that the music was 130 bpm. However, the snare drum pattern in N2S puts it at 65bpm.

Now, applying the same principle to Two-step, Pony, and Polka, we find that the snare drum pattern leads to an inferred tempo of around 200 bpm -- and over that number for Pony and Polka. Also, in some songs you wil hear the same drum pattern appear across different dances. For instance, Clint Black's No time to kill uses the typical polka pattern, only slower. So, shouldn't that imply that polka is faster than two-step?

Of course, despite these sort-of hard arguments for the "true" count of a dance, practical considerations of choreography may dictate a pragmatic count that is different from the one found from musical considerations. For instance, counting two-step as 1&23 has the great choreographical advantage that you step on every "beat", which makes mapping a routine a lot easier.

In ballroom dance and related forms such as latin, swing, country, all dances have either three or four beats to the bar. In folk dancing on the other hand, in particular non-western folk dancing, one can encounter bars with five, seven, or nine beats.

Even apart from dance music, time signatures with other than three or four beats to the bar are quite rare in western popular and classical music. The best known exceptions are some compositions in five quarter time: the theme from the tv series Mission Impossible and the jazz standard Take Five played by the Dave Brubeck Quartet, both with a 3+2 feel, and the second movement from Tchaikovsky's fifth symphony, which has a 2+3 feel.

The term "syncopation" is used both in music and in dancing. The dance meaning of the term is derived from the musical meaning, but there is considerable difference in the details. In both cases, the meaning could be described as 'putting notes/steps where they were not'. In music, syncopation refers to taking notes that would be on the beats and moving them forward or back to fall in between the beats. In dance, syncopation involves not moving steps about, but rather adding them in between beats.

In music, the intended meaning of syncopation is to establish a rhythm counter to the original rhythm. Thus, syncopated rhythms can be considered as a shift of an original rhythm that was completely on the beat (Movie: small and large). Another way of stating it is that normally unaccented, or weak, beats are now accented. Here is a definition taken from the New Grove Dictionary of Jazz:

In measured music an effect of rhythmic displacement created by articulating weaker beats of metrical positions that do not fall on any of the main beats of the bar, while stronger beats are not articulated.

Slightly more elaborately, here's the definition from the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians:

The regular shifting of each beat in a measured pattern by the same amount ahead of or behind its normal position in that pattern [...] Syncopation, as it is most widely understood, is restricted to situations in which the strong beats receive no articulation. This means either that they are silent [...] or that each note is articulated on a weak beat (or between two beats) and tied over to the next beat [...]

Lots of words, eh? If you keep in mind that in spirit a syncopation is the establishment of a shifted pulse, here is *cough* Victor's 99% infallible syncopation recognition criterion: A rhythm is syncopated if there occur two consecutive notes in between beats.

In dance, the term syncopation is also used, and it refers to dance steps occurring in between beats. For example, in west coast swing there is a popular variation on the basic footwork where the step-step on beats 1 and 2 changes to point-step-step in the 1&2 rhythm. Here, the step action that would normally occur on the first beat has shifted back by half a beat. However, unlike in musical syncopations where the beat itself would have no action associated with it, here another action is added on the beat.

You could also say that an action has been added in between the beats: there used to be two actions and now there are three. This adding of steps also occurs in other dances, for instance in waltz 12&3 is a syncopated pattern.

Another form of syncopation is to take an in-between-beats action and move it to another location. For instance, again in west coast swing -- the dance that virtually has a patent on syncopation -- the first four steps of a pattern 12 3&4 can change to 12 &34. Here, the location of the in-between-beats action has moved forward one beat.

Here is the definition by dance authority Skippy Blair:

[...] the rearrangement of the weight changes within the 2-beat Rhythms. [...] Stepping before the beat [...] and then stepping again, or doing something else on the actual beat of the music. Example: count "&a1". Lift your knee on the "&", step on the "a" and "kick" on count "1".

This then seems to be the interpretation of the term "syncopation" in dancing:

However, none of the syncopated dance rhythms above would be considered syncopated in music, because no action appearing on a beat has been removed. It is very rare for there to be a dance action in between two beats without there being an action on the second of the beats. The only true syncopation I have ever come across in dance is a timing change in hustle, where the normal 23&1 was replaced by 2&(3)&1 without any added actions on beat 3.

In summary, dance syncopations and musical syncopations have similarities in spirit, but large differences in practice.

Footnotes

Ok, not quite for chacha and international rumba; we will get to that later. Even in those dances, though, the basic rhythm repeats every bar, and the footwork every other.

This file is part of "Feel The Beat", a musicology course for dancers, by Victor Eijkhout (victor at eijkhout dot net), who appreciates being sent additions or corrections on the material in this course. Copyright 2000/1 Victor Eijkhout.

You may link to this page but you may not make copies for private use in any form, electronic or physical. (Obviously the copy in your browser cache is needed, but you must let this be purged in the normal way.) Reproduction in any means such as book or CDROM is especially not allowed. When you link to this page, the page may not be displayed in a frame: use the full window, or open a new one.

It goes without saying that Victor takes no responsibility for any inaccuracies in the information presented here or for any use or abuse of this information. Victor is neither a doctor nor a lawyer, so do not follow his advice.

URL: http://www.eijkhout.net/ftb/text_files/Beats.html

Last modified on: Sunday, May 6, 2001.